Bulletproof Shoulders: How to Get Out of Pain and Keep Training

The shoulder is one of the most remarkable joints in the human body. It gives us the ability to hang, press, throw, climb, swim, and support load overhead. It is also one of the most commonly injured areas I see in CrossFit and athletes who spend a lot of time in the gym.

Most shoulder pain is not a “shoulder-only” problem.

It is usually the result of poor posture and movement options, limited mobility, inadequate stability, and cumulative stress over time.

The good news?

With the right approach, many shoulder issues are preventable—and even chronic, nagging pain can often be reversed before they become true injuries.

Let’s break this down.

The Shoulder: Built for Mobility, Not Stability

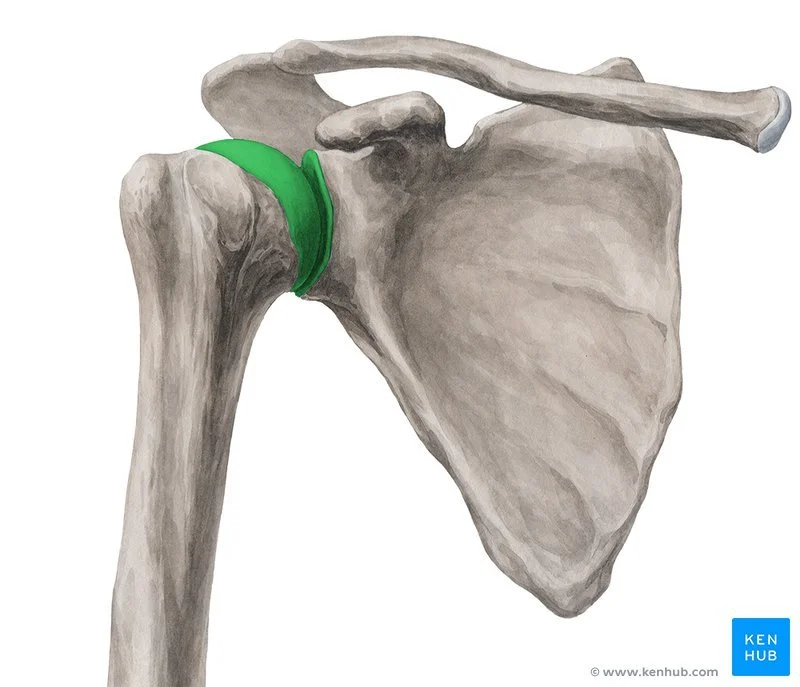

When people talk about the “shoulder joint,” they are usually referring to the glenohumeral joint—where the ball of the humerus sits in a relatively shallow socket on the scapula.

Glenohumeral Joint

This design is often compared to a golf ball on a tee.

This shallow ball-and-socket design gives us enormous mobility, but limited structural stability. Unlike the hip—a much deeper ball-and-socket joint with significant bony congruency—the shoulder relies heavily on active stability, meaning your muscles.

Specifically:

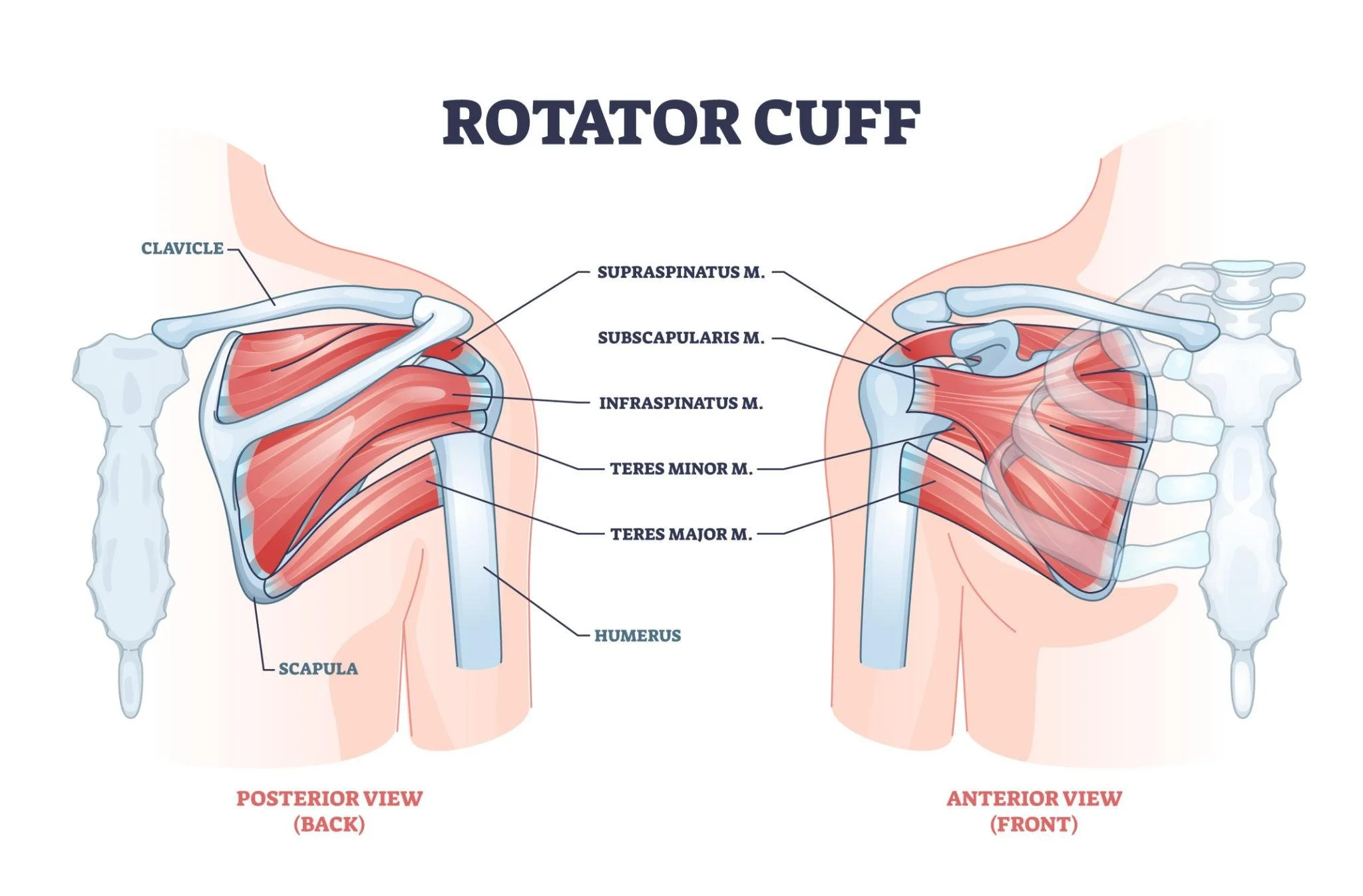

Rotator Cuff

These muscles help “hug” the head of the humerus into the socket and keep the joint centered.

Rotator Cuff: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis

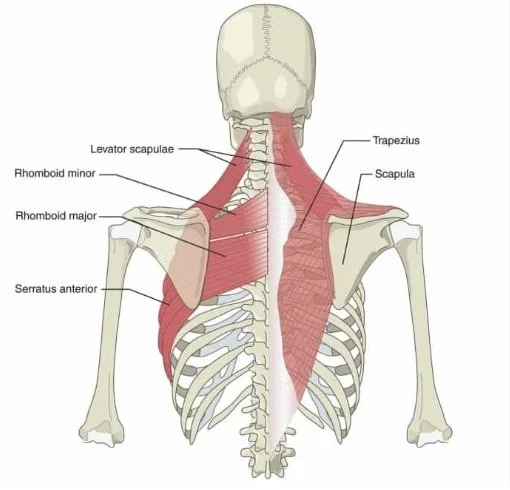

Scapular Stabilizers

These muscles control movement and positioning of the shoulder blade.

Scapular Stabilizers: mid/lower trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids

Regional Interdependence: The Shoulder Rarely Acts Alone

In addition to local stabilizers, shoulder health is profoundly influenced by posture and how the rest of the body contributes to movement.

Key influences include:

Thoracic spine mobility (especially extension and rotation)

If you don’t have adequate thoracic extension (think: ability to sit up tall), more motion is forced to come from the shoulder.Rib cage position and breathing mechanics

If your rib cage lives in a flared, overextended position, your rotator cuff will struggle to center the joint.Scapular control

If the scapula does not upwardly rotate or posteriorly tilt, overhead motion becomes compressed at the front of the shoulder, often causing pain and dysfunction.

In other words: the shoulder is only as healthy as the system it lives in.

4 Exercises for Shoulder Health

If we want to optimize shoulder health, we must strengthen our stabilizers and address posture and mobility.

These are foundational movements I regularly use with athletes who want to train hard and stay durable. They can also be helpful for addressing nagging shoulder pain. If you are concerned about your symptoms, see the section below on when to seek professional help.

1. External Rotation

Rotator Cuff Strength

Why it matters

Improves the shoulder’s ability to center the joint and tolerate load.

Focus on

Keep the elbow pinned at your side. Rotate the arm outward slowly and control the return. You should feel this around the back of the shoulder and into the lateral deltoid.

Dosage

2–3 sets of 10–15 reps, 3x per week

Light resistance (small stabilizing muscles)

Examples:

Banded External Rotation

Banded Rotator Cuff Pumps

2. I’s + T’s

Parascapular Strength

Why it matters

Strengthens mid and lower trapezius and reinforces healthy scapular positioning.

Focus on

Light load, perfect control, no momentum. Initiate movement from the shoulder blades.

Dosage

2–3 sets of 10–15 reps, 3x per week

Examples:

Banded I’s & Banded T’s

Chest-Supported I’s & Chest-Supported T’s

3. Bench Stretch or Banded Lat Stretch

T-spine & Lat Length

Why it matters

The lats are large muscles heavily used in rowing, pulling, deadlifts, ski erg, and many other athletic movements. When they become stiff, they can significantly limit overhead mobility and increase stress on the shoulder.

Limited overhead range is also highly influenced by thoracic spine mobility—a topic deserving its own deep dive.

Focus on

Use your breath to help expand the rib cage and deepen the stretch.

Dosage

2–3 minutes, 3x per week

Examples:

Bench Stretch for Lats and T-spine

Banded Lat Stretch at Rack

4. Pec Smash

Pectoral Muscle Length

Why it matters

Overactive pectorals can pull the shoulder forward and limit overhead mechanics.

Focus on

Find tight or tender areas and use slow breathing. Gently move the arm while applying pressure. Explore the region without forcing into sharp pain.

Dosage

2 minutes per side, 3x per week

Examples:

Pec Minor Smash at Wall

Pec Smash with Orb

When to Seek Professional Help

Early evaluation often leads to faster resolution, fewer training interruptions, and a clearer plan forward.

Consider seeking professional help if you experience:

Pain lasting longer than 7–10 days despite reducing training volume

Pain that worsens with warm-up rather than improves

Night pain or disrupted sleep

Sharp pain, catching, clicking, or feelings of instability

Loss of strength or range of motion

Recurrent flare-ups with the same movements

Pain following a fall, collision, or traumatic event